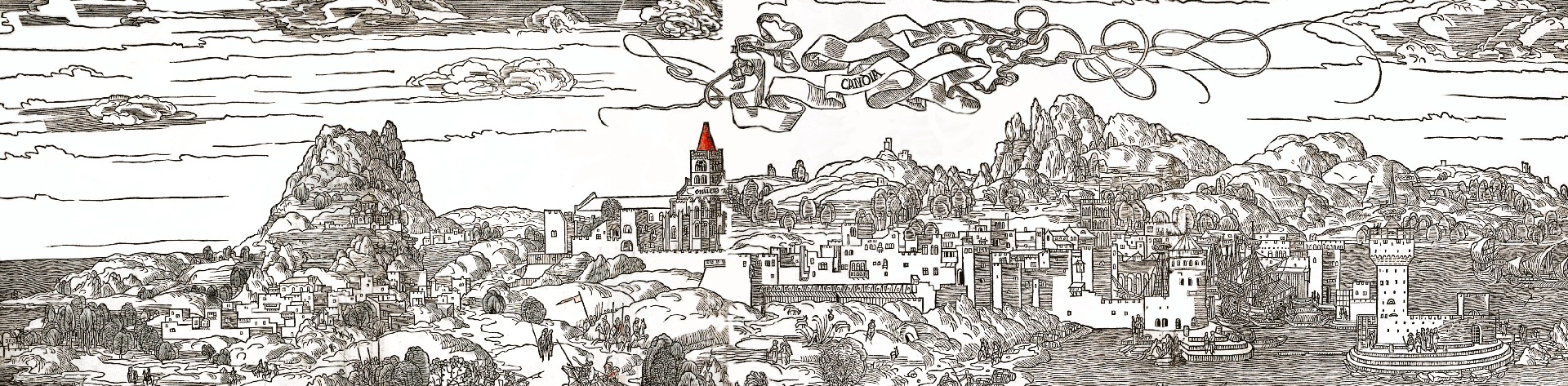

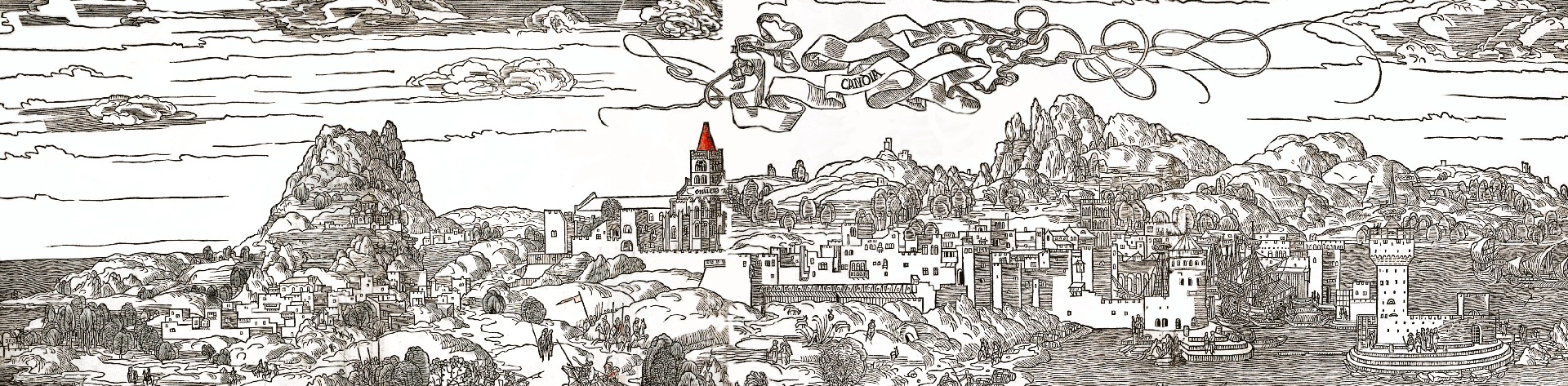

The ottomans maintained the fortification and

the urban fabric of the Venetian Candia. In fact, given the importance of the

city as a fortress, there began, after the establishment of the new

authorities, a systematic recording of the most important public and private

buildings, the underground grain storehouses, the water cisterns and the

churches. Immediate repairs were carried out on the walls along with some minor

additions (the St. Andreas bastion, the small Koules etc.), the water supply

from the springs of Archanes (Kemer Suyu), which was cut during the siege, was

restored and new water collection and distribution cisterns were built.

Additional water supply for the mosques, dens, baths, jets and fountains

(charitable, public and private) of the city was attempted from the smaller

springs of the surrounding area. A great utilitarian

project of the time was the construction of the drainage system which included

the building of two closed masonry culverts in key city locations. The ottoman

troops were housed in the venetian barracks of St George (Imperial

Janissaries), those at the gate of Jesus and the «Haunt of the Pit». In

the place of the monastery of Akrotiriani the kisla of the local janissaries

was built, while prisons and public granaries continued to operate in the

Volonte gate of the arab-byzantine- old venetian walls and the adjacent

venetian Fontaco to the east. The other public buildings were used to

house senior ottoman officials who were granted imperial permission by Kiopruli

himself to convert fifteen Christian churches, and later a further eight, to

mosques provided they dedicated residential property for their maintenance.

Furthermore, a substantial number of small churches like Panagia Faneromeni in

Martinengo, were converted to houses of prayer (mescid) and dens for the Muslim

clergy. A different case is that of the large den of the Mbektasides of Ali

Dede Chorasanli, which was built during the siege in the place of the venetian

settlement ´Kaiafa´ in present day suburb “Ampelokipi”. Smaller churches

and some of the private chapels in the luxury homes that came under ottoman

officials were also converted into baths (hamams). We also know of the

existence of nine public baths. The city's reconstruction projects were carried

out in their entirety by the Armenians miners of the Ottoman army and some

local specialized castle-builders.

With the exception of the small one-room homes

in the poor districts of the city’s fringes, Renaissance Venetian mansions

uniquely interacted with houses of Balkan architecture and neoclassical

mansions, thus transforming the cobbled alleyways of the city into carriers of

its legend. Behind the wooden lattice screens of the windows and confined

within the high walls that surrounded the courtyard, Ottoman houses enclosed

fairytale worlds. Painted wooden ceilings, mousantres and partitions, and

magnificent pebbled yards with hazinedes, wells and peacocks in lush vegetation

was the magical image of Candia’s East.

Τhe old Jewish community and the synagogue remained within the city, in

the area between the mosque of Sultan Ibrahim (Venetian monastery of St.

Andreas) and the gate of sand (Kum Kapu) of Dermata bay.

The wall towers of the Holy Spirit (Τasli Ntambia) = rocky rampart),

Pantocrator and Aghios Nikolaos and the St. Demetrious (Ακ Ntambia = white

rampart) fortress were preserved on the outside of the strong city walls. The

guarded area of Top Altis was situated inside the moat of the fortress of

Candia, where the land was from the beginning divided into areas for crop and

animal husbandry and burials. So, the two large Muslim cemeteries were built close

to the gates of Pantocrator and Jesus, among lush vineyards were.

Finally, because the gates of the castle were

closing at sunset and opening again at sunrise, those who failed to get in the city in time could spend

the night in vaulted lodgings situated near springs that were especially

adapted to house them and their animals, such as the one at “koroni Magara” and

“koumbedes” on the road to Chania.

The "most beautiful city of the

East", often suffered natural disasters. Earthquakes leveled the mighty

buildings and fires swept the masterpieces of Balkan architecture with the

wooden floors. Finally, in the 20th century, "expansion",

urbanization and modern lifestyles further wounded the historic character of

the city.

1. gr// Επιτροπάκης Π., gr// Το Ηράκλειο στους Οθωμανικούς χρόνους, gr// Η Οθωμανική αρχιτεκτονική στην Ελλάδα, gr// Αθήνα, gr// 2008, p. gr// 396-397 More

| 6. The Great Castle (Kandiye) | |

|---|---|---|

| 6.1 Crete during the Ottoman occupation | |

| 6.3 The rebellion of Daskalogiannis (1770) |