The continuous habitation and the numerous physical

and human catastrophes destroyed almost without a trace the ancient city of Heraklion, which was mentioned by Strabo as a port of Cnossos. The small natural harbor and the

sandy haven were probably exploited as soon as the Minoan period, since scatter

findings from the Minoan to the Roman period have come to light. During the

Hellenistic period the city received mighty fortification walls and had a

significant extent. During the roman period it was considered to be one of the

few well-protected harbors of the northern coast of the island (Stadiasmus Maris Magni). A luxurious

roman villa with mosaic floors, burials with lavish offerings, scattered

sculptures, a huge column capital in its second use and several inscriptions

testify the wealth of the city during the Roman period. In the Early-Byzantine

period the city became a bishopric seat. In the Synodical catalogues it was mentioned

either as Heracleae (343 A.D.) or

later as Herakleioupolis (7th Ecumenical Synod).

Excavations

have brought to light a vast amount of findings (architectural sculpture,

pottery, coins and small findings), but only a few relics of constructions.

From the middle of the 7th c. (654 A.D.) the city begun to feel threatened

by the presence of the Arabs in the Aegean Sea. In order to prevent a

catastrophe, the Byzantines decided to fortify the city with new walls, using

blocks from the Hellenistic enceinte, just like they did in other important

settlements around the island. Nevertheless, the sturdy enceinte, its

quadrangular defensive towers and the moat, which led the Arabs to name the

city Rabdh el Khandaq (The Fortress

of the Moat), were proved ineffective. The Arabs debarked on the island from

the South, probably the area of Keratokambos, and gradually conquered it until

828. For the next 150 years, Heraklion, which was the last to fall, became the

base of the Arabic raids and trade around the Mediterranean. A large amount of

Arabic bronze coins and pottery of high quality, imported both from the East

and the West (Spain), testify the long lasting presence of the Arabs in the

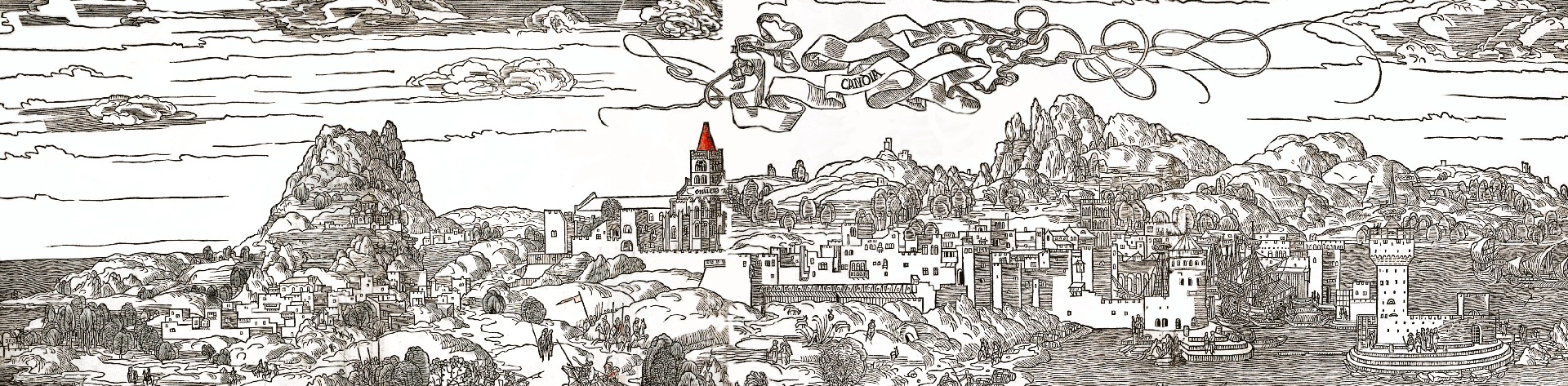

city, which left its indelible mark to its name; Khandaq (moat, trench) became Chandax

for the Byzantines and Candia for the

Venetians.

The loss of Crete was a

severe strike to the Byzantine predominance on the Mediterranean. Its recapture

though was even harder. After a series of wasted efforts, in 961 the Byzantine

general of the army, and later an emperor, Nicephoros Phocas, managed to recapture

the city, by mining its walls. The city gradually gained back its wealth and up

to the end of the 12th c. knew a significant commercial and economic

development. Nevertheless, just before the Fall of Constantinople to the Franks

in 1204, the deposed Byzantine emperor Isaac II offered the island of Crete to

Boniface of Montferrat as a reward for helping him regain the throne. Boniface

in his turn sold the island to the Venetians. After a short capture by the

Genoese Enrico Pescatore and his pirates, in 1211 the city came under the rule

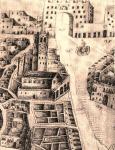

of Venice. Candia became the capital

of the Venetian Kingdom of Crete, the most important trade station of Venice in

the Eastern Mediterranean, a place where literature and fine arts flourished

for many centuries.

When Cyprus fell to the Ottomans in 1571, Candia became the sole military

base of Venice in the East Mediterranean. The Venetians tried to protect it

with a new, huge enceinte, which gave the city its latest name: “Megalo Kastro” (The Large Fortress). But

after 21 years of fierce siege and resistance, which is known as “the Cretan

War”, in 1669 the last defender of the city Francesco Morosini was forced to

surrender it to the forces of the Sultan.

| 1.1 Candia under the Venetian occupation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2 The public buildings | |

| 1.2.1 Ruga Magistra (Maistra) | |

| 1.2.2 The Ducal Palace | |

| 1.2.3 The Venetian Loggia | |

| 1.2.4 The Warehouse for the Cereals (Fondaco) | |

| 1.2.5 The Gate “Voltone” | |

| 1.3 The orthodox churches | |

| 1.3.1 St. Catherine of Sinai | |

| 1.3.2 Saint Anastasia | |

| 1.3.3 The Church of St. Mathew, dependency of Sinai | |

| 1.3.4 St. Onouphrios | |

| 1.3.5 Virgin of the Angels (Santa Maria degli Angelis in Beccharia) | |

| 1.3.6 Church of the Virgin Pantanassa (southern aisle of the old Metropolis / old church of St. Menas) | |

| 1.4 The Latin Churches | |

| 1.4.1 The basilica of St. Marc (ducal church) | |

| 1.4.2 The church of Saint John the Baptist | |

| 1.4.3 Saint Paul of the Servites (Servants of Mary) | |

| 1.4.4 The monastery of St. Francis of the Franciscans | |

| 1.4.5 Santa Maria di Piazza (Madonina) | |

| 1.4.6 The Monastery of St. Peter of the Dominicans | |

| 1.4.7 The Church of St. Titus (Latin Archdiocese) | |

| 1.4.8 The church of San Salvatore | |

| 1.5 The fountains and hydraulic works | |

| 1.5.1 The Fountain of the Ruga Panigra (Strata Larga) | |

| 1.5.2 The Bembo fountain | |

| 1.5.3 The Morozini Fountain | |

| 1.5.4 The Priuli fountain | |

| 1.5.5 The Sagredo fountain |