1648

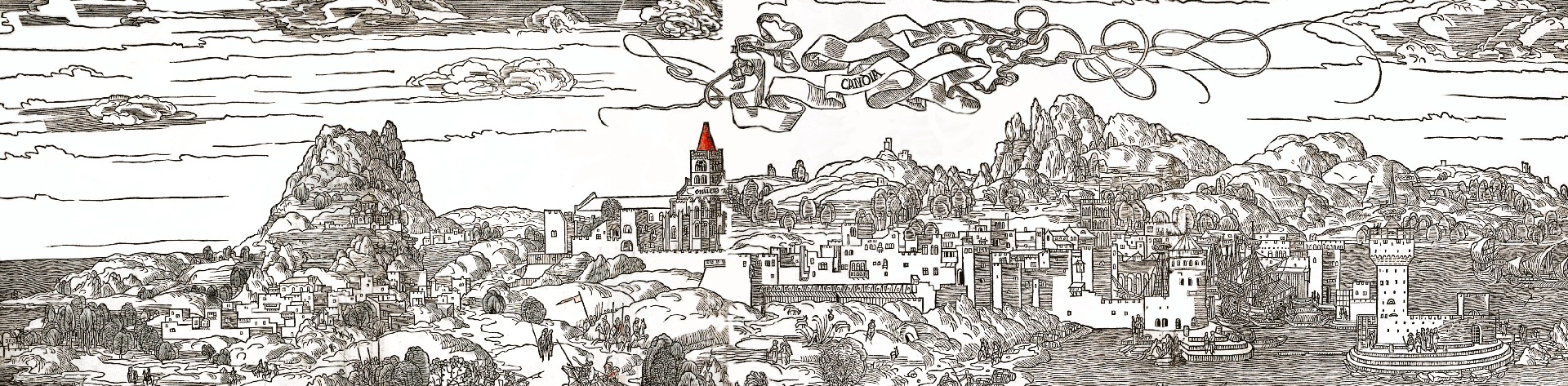

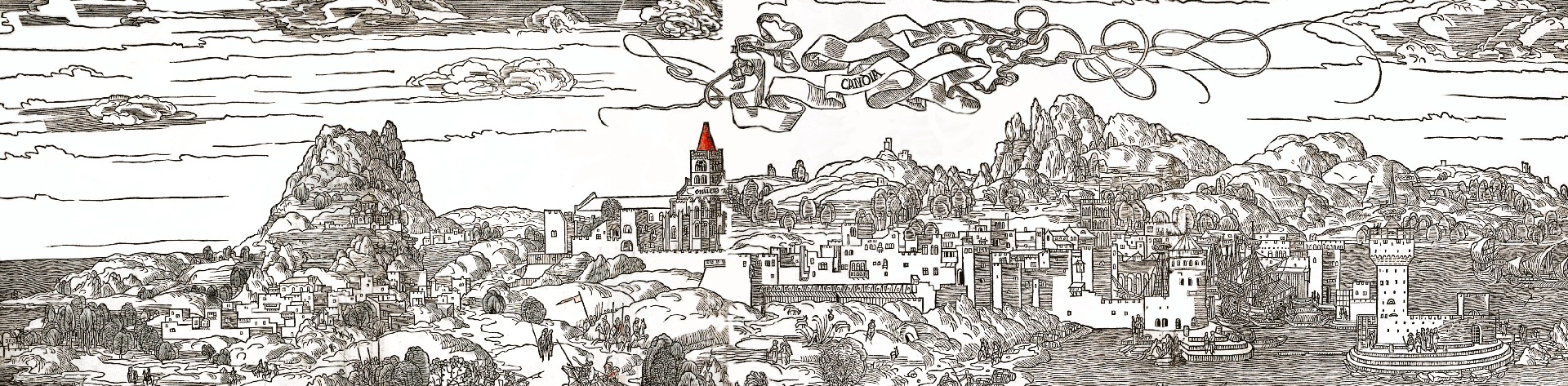

: When the Ottomans,

with Gaze Hussein Pasha at the head, arrived in

front of the huge city walls, they didn’t attack the city wright away. Their

heavy canons had to be debarked in Chania and pulled by captives through the

mountain trails of the northern coast to Candia, since no secure place of

debarkation existed in the vicinity of the city. Until then they camped to the

West of the Fortress, by the river Giofyros, and begun to be prepared for the

siege.

They

started by cutting off the water supply of the Morosini aqueduct, which had its

springs by the village of Archanes. They also tried to reach the Fortress

through burrows dug by special under-miners, such as Armenian gold-miners, parallel

to the section of the wall that they tried to reach. The method failed, since

they were not yet familiar with it. The tactic of undermining by the besiegers

and cross-undermining by the besieged, as well as

the merciless

bombarding, would be the main characteristics of

the siege of the largest defensive work of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Heavy

canons arrived in March 1648 and were installed on the hills around the city.

For the next 21 years the only way out for the besieged citizens of Candia

would be the sea. The Ottomans initially chose to attack the Fortress from the

South and southeast,

which was the section of the most powerful bastions (Vitturi, Jesu,

Martinengo), since they thought erroneously that the higher level of the ground

outside the moat should give them an advantage. The first severe attack in June

1648 was successfully confronted by the defenders of the external fortress of

St. Demetrius. But damages were caused to the spear and the body of the

Martinengo bastion, helping the Ottomans to climb for a while on the bastion,

before they were repelled. Damages were also caused to the flank of the Jesu

bastion. The curtain wall between the bastions of Jesu and Vitturi was fiercely

bombarded but not conquered.

After

his failure, Hussein withdrew his army to the hills

of Marathitis, were he set a camp. The defenders made repairs to the walls and

constructed additional defensive works during the winter.

1649: Attacks

were repeated from August to early October of the next year, against the same

parts of the walls and the SW side of the Fortress, from the bastion of

Martinengo to the bastion of the Pantokrator (Panigra) without any success. In

the beginning of the winter the Ottomans were withdrawn, realizing that the

conquest of Candia would not be an easy case. Since this would be a

long-lasting siege, they decided to construct permanent bases and shelters to

be protected by counterattacks.

In the 28th of February

1649 the Sultan ordered the construction of three small fortresses around the

walls of Candia, one to the East, near the lazaretto, one to the South and one

West of the river Giofyros. At the same time begun the construction of the

fourth, larger fortress, which

was to act as the headquarters, on the hills of Brussa, the actual

village of Fortezza, which took its modern name by the fortress itself. The

fortress was called Enantia or New Candia or Inadiye or Kale-I-Cedit (New

Fortress), but the construction was negligent.

1649-1666: From

1649 to 1666 generated war inactivity occurred. The city remained besieged and

the only breakthrough, which was the sea, became more and more hard. In 1666

the situation was suddenly changed. The Sultan had already recalled Hussein, he

had taken his head off as being responsible for the failure of the siege and he

had replaced him with Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, the so-called Faisal (fair), a

skillful, ambitious and cruel man, which was meant

to be the fatal person for the city. Against him should stand Francesco

Morosini, the efficient general of the city’s army

and the most powerful fortress

in the Mediterranean Sea. The dramatic epilogue of the siege had already begun

to be written.

Köprülü debarked in Chania

in early November 1666 and arrived in Candia soon after that. Until the next

spring he made careful preparations, moving his headquarters to the fortress of

Giofyros, which he protected from the East with a moat, fortifying the areas of

his powder guns, creating a smelter of cannons near Cnossos and a powder manufacture

near Fortezza and ensuring the supply of his troops from the harbors of

Tsoutsouros, Matala and Ierapetra.

1667: In the

28th of May 1667 Köprülü attacked the SW side of the Fortress, from the bastion of

Martinengo to the bastion of St. Andrew, with 300 canons. The Ottomans managed

to destroy the wall holding the bank of the moat opposite the bastion of

Pantokrator, to occupy the external fortress and to enter to the moat in front

of the bastion, which was now under deep pressure. The attacks went on and on

until November.

In the 15th of

November 1667 the Venetian mechanic Andrea Barozzi defected to the Ottoman side

and provided Köprülü with details on the construction and status of the walls,

revealing the weakness of the two sea-side bastions, the Sabbionara bastion and

the bastion of St. Andrew. These two bastions, due to their position, were not

complete, since they possessed one lobe and one low terrace for canons each ; they were lower than the

rest and most of all, they could not be cross-undermined by the defenders since

the bastion of St. Andrew was constructed on a rocky ground and the bastion of

Sabbionara on the sandy beach. Barozzi also consulted the Ottomans on the

undermining method.

Under Barozzi’s instructions

the Ottomans revised their attacking attitude and turned their gun forces

towards the northern edges of the inland walls. Ιn the 10th of

November 1667 the bombarding of the bastion of St. Andrew begun. By the 10th

of December, external fortresses begun to be constructed opposite the two

sea-side bastions. The besieged understood the change of the attacking attitude

and tried to take defensive measures, without success. The defenders were by

then both outnumbered and exhausted.

1668: In the

11th of June 1668 a new attack was fired, this time against the

bastion of Sabbionara, causing a breakage of 140m. in wideness on his flank. In

respect, a breakage of 160 m. was caused on the bastion of St. Andrew. The

defenders tried

to construct retreat dikes.

1669: By January 1669 the situation for

the besieged was tragic. The bastion of St. Andrew and the first dike of

defense, the so-called “wall

of the Frenchmen”, were

conquered by the Ottomans and the defenders had retreat behind the second dike

of defense. On the bastion of Sabbionara, in the place of the flag of St. Marc,

the flag with the double ax, the emblem of the Janissaries, was weaving. Soon

the flags of the seven Janissary troops, the famous “Seven Axes” should be on

the bastion and to the west of it. The second defense dike broke as well.

The

city of Candia was doomed. The heroic sortie of the French, who run to help

under the admiral Duke de Beaufort and Duke de Navailles failed, as did the

bombarding of the ottoman troops by the fleet of the Christian forces. The

detonation that sunk the flagship “La Thérèse” put an end to the effort.

Trying

to avoid the plundering and the massacre, the

last heroic defender of Candia Francesco Morosini chose the capitulation.

According to the terms of the treaty, signed after long and hard negotiations

in the 16th of September 1669, Venetians surrendered the island to

the Ottomans, except for the fortresses of Grambussa, Suda and Spinalonga and

in return the citizens of Candia should be given the time to abandon the city,

carrying with them their guns, their treasures and their documents. Thanks to

this deal the valuable state archives of Candia were safely transferred to

Venice. Later Morosini was accused by the State of Venice of betrayal, to be

finally declared innocent. Nevertheless, the love for the city he defensed for

21 years can be easily estimated by the Cretan symbols on his flag, designed by

the famous Cretan painter Victor, actually exhibited in the Museum of Corer in

Venice, and the donation of his coat-of-arms and crown to the Virgin

Messopantitissa, the miraculous icon of Candia, which was also transferred to

Venice and it is hosted today in the church of Santa Maria della Salute.

When

the Ottoman troops entered Candia in the 4th of October 1669 the

city was empty. The cost of the loss in the mind of Candia’s citizens, who were

forced to abandon it after 21 years of siege, hunger, thirst and furious

resistance, can be counted only through the mourning poetry. Perhaps no other

city in men’s history was praised and mourned as much as did Candia in the

poetry of Manuel Zane Bounialis:

Oh

my glorious Castle, I wander if those who survived

are mourning and feeling

homesick for you.

All citizens of Candia should be dressed in black

every day they should mourn and they should

never sing

men,

women and boys and every girl

they ought to show

that they lost such a homeland.

| 5. The “Cretan War” | |

|---|---|---|

| 5.2 Cretan War and sank of La Thérèse | |

| 5.3 The evacuation of Candia | |

| 5.4 The Cretan War in the Literature | |

| 5.4.1 Anthimos (Akakios) Diakrousis | |

| 5.4.2 Marinos Tzanes Bounialis |